For my research, I investigated whether media coverage of poverty is necessary, the ethical implications of objectifying people living in poor conditions, and to determine whether we can understand the seriousness of poverty without seeing it through forms of videos and images.

For my investigation, I completed both primary and secondary research to get a better understanding of the question. I used secondary research because it can save time and money as there is already information provided that I can analyze. Some of the information that I gathered were from journals, news articles, and already available interviews online from people who have experience working in environments where they’ve had to take videos or pictures of poor people living in dreadful conditions. These interviews give a professional and personal perspective of the ethics behind “poverty porn”. And for my primary research, I created a survey asking seven questions about media coverage on poverty, and these questions were answered by fellow BCM students.

There is a lot of power that comes from imagery. Images bring to light things that are hard to understand if you can’t see it for yourself. The National Press Photographers Association’s Code of Ethics wrote:

“Photographic and video images can reveal great truths, expose wrongdoing and neglect, inspire hope and understanding and connect people around the globe through the language of visual understanding. Photographs can also cause great harm if they are callously intrusive or are manipulated.” (Bersak 2006).

This suggests that photographic and video images can be very necessary to expose injustice, however it can also create harm if the imagery is manipulated to fit a specific narrative.

Although photographs allow people to see into a world of poverty which may not have been understood without visual evidence, there are instances where imagery of the poor can become problematic and incite more harm than good. Through my secondary research, I found a journal article discussing the ethical issues in photojournalism. I found that during the 1930s, at the time of the great depression, media professionals in the USA would manipulate photographs, a phenomenon known as “scene preparation.” The photographs taken were not of the poor or beggars as they really were on the street, but a manipulation of the scene. They were placed in specific positions creating an, even more, sever image of the crisis. This shows the objectification of the poor as they are being used to tell a fabricated story where the real crisis is being over-looked (Zguri, 2014).

Various charities and non-profit organizations believe the most effective way to incite sympathy in order to get donations from people is by using scene preparation and manipulate imagery as a tactic to evoke pity and charity. However, these types of images fail to capture communities in their real state and thus creating an enormous lie.

A photographer by the name of Duncan McNichol was part of a “Perspectives of Poverty” project where he photographed a man named Edward Kabzela of Chagunda Village, Malawi. In one of the images, Edward was portrayed as a hopeless, dirty, hungry, and impoverished beggar, however, this portrayal of Edward was inaccurate. In reality, he is a very successful area mechanic and grower of tobacco and works for a basket weaving business.

Edward explained, “NGOs come to the village here to take pictures of people. At church, at the market, on the road, at meetings. Only people who are dressed poorly.” “These images are unfair to the local population and have “become a marketable commodity. They are blown up and displayed at fund-raisers by NGOs, donors, and UN agencies; they help organizations to stay in business. The more graphic they are, the more money they help to raise” (UniteForSite, N.P). Although the intention behind the photographs is trying to invoke positive change, donations, and charity, the way it is done is unethical and sometimes tasteless. Scene preparation and photo manipulation can cause a lot of harm as it can create a stereotypical view of a community or not show aspects that really need attention. It all becomes a fabricated story that takes away from real issues.

Occasionally, fabricated and manipulated images of poverty can cause a stereotypical view of a community, and therefore that community can’t thrive without labels being thrown at them. Many researchers argue that the image of Africa presented through the Slovenian media, aid/charity organizations and academia is biased and one-dimensional. The images are often only expressed in a way to emphasize war, conflict, poverty, disaster, passivity, despair, and most importantly the opinions of people from Africa are rarely ever voiced. These constant images become misleading and stand in the way for development in Africa as it gives Western Societies more power and dominance. (Dolinar, Sita, 2013). It is important to be aware of the struggles people face in Africa, however, poverty porn has become so extreme that people only associate Africa as a deficient continent and thus creating negative stereotypes. A twitter user by the name of Diana Salah started a hashtag on the platform called #TheAfricaTheMediaNeverShows to highlight what is not shown in the media about the continent and challenging the stereotypes given to them by Western society. This hashtag accumulated over 42,000 tweets and retweets where users posted images of “grand architecture, fashion, cuisine, culture, engineering, universities, diamond mines and female heads of state.” (Dortonne, 2016). Africa is changing and evolving so rapidly, but its progress is not shown in the media as much as it should because “poverty porn” does not allow Africa to thrive.

An issue that is very prominent in photojournalism is the subject of consent. There are often times when photojournalists do not ask for consent before an image is taken and therefore that image could become humiliating and dehumanizing. A New York Times photographer going by the name of Chester Higgins Jr. said, “It’s time to change the visual conversation.” Higgins has traveled to Africa many times since 1971 where he’s taken trips along the Blue Nile, through Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, to “make photos,” live and create relationships. He has explained that he frequently sees pictures being taken without the consent of the subjects. Due to the lack of consent, the subjects that are being photographed are humiliated and dehumanized. He said, “A distinct mark of poverty porn advertisements and photographs made by non-African photographers is the lack of decency, dignity, virtuous character, or that it shows the subjects’ most vulnerable moment” (Dortonne, 2016). These images can later haunt people in the future and not allow them to move past the tragedies in their life. Birham Woldu became the “face of Live Aid” as a starving three-year-old in 1984, as she was a child, she could not personally give consent to her photograph being taken. The picture did wonderful things to her life such as put her through school, however, Woldu states that there are also had negative impacts on her life due to the photograph. She says: “For me, personally, Live Aid has done nothing. I am branded as the symbol of Live Aid due to the image of the 1980s. My stories are well documented and have reached the skies. But I live underground. The state I am in at this moment is miserable. I do not have a job and I cannot support my family on my own” (The Guardian, N.P).

Through my research, I accumulated interviews/personal notes from photojournalists where they talk about their experiences taking images of poverty and how it affected them personally. The question that I felt needed to be addressed is whether photojournalists themselves believe it is ethical to take images displaying homelessness, warzones, famine, etc. Kevin Carter was a notorious photographer that took countless images of poverty/famine which later affected his mental health. He committed suicide the year he won an award for the image of “The vulture and the little girl.” In his suicide note, he wrote:

“I’m really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist… I am depressed… without phone… money for rent … money for child support… money for debts… money!!!… I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain… of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners…” (Rare Historical Photos”.

His note suggests that the images he took where unethical which is why his mental health deteriorated.

However, Shehab Uddin a former newspaper photographer had a completely different experience taking images of poverty. Uddin says that he took a different approach when taking these images. He states in an interview that: “When photographers visit a country like Bangladesh, we don’t bother to ask permission from the people we want to photograph,” Mr. Uddin said. “We have the power, with thousands of dollars of gear, nice clothes, and a good education, and we think we have every right to photograph.” However, Uddin decided to take a more immersive and collaborative approach, different to how most photographers conduct their work. Not only did he ask for consent before taking pictures of poor societies, but he also moved in with several families so they could have input into what images he would display in their communities (Estrin, 2015). This gave people in poverty a sense of control of their own lives where they were able to choose photographs themselves, allowing them the option to create their own narrative about the lives they live without manipulation. This ethical approach suggests that there are better ways to show images of the poor in the media that does not dehumanize the subjects.

There is also an argument to be made that images can have a great impact on people living in poverty. For example, After James Nachtwey, an American photographer took pictures of famine in Somalia, The Red Cross was bombarded with public support in what was then its largest operation since WW2 (The Coversation, 2018).

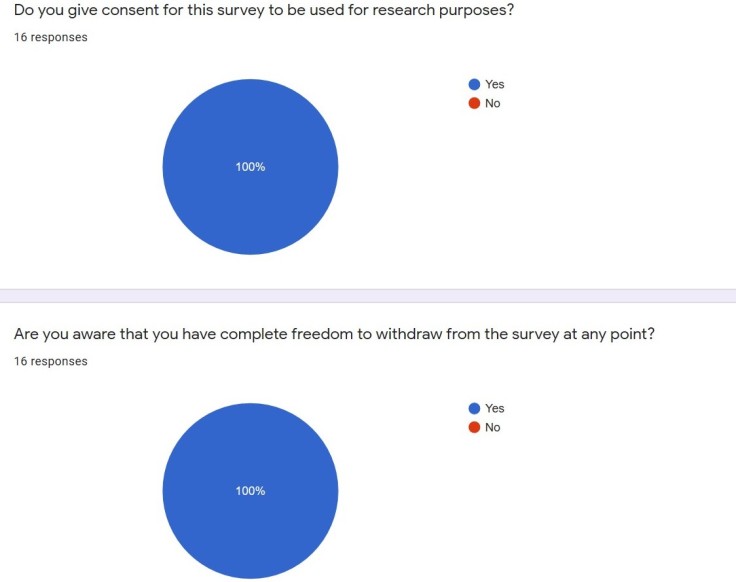

For the second part of my search, I conducted a survey for people enrolled in BCM subjects around the University of Wollongong, the aim of the survey was to compare the findings from my secondary research from scholars and professionals to every-day people and what their views are on media portrayal of poverty. In the survey, I asked six questions and received sixteen responses. Before answering the questions, the people that took the survey were given background information about the survey and an opportunity to give consent to use their responses in the final essay.

With the new age of technology, the imagery of poverty and “poverty porn” shown in media has become exponentially high. With social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram being used as a tool to spread awareness, a new wave of “digital activism” has been created. However, is the seriousness of poverty really understood?

My survey results show that 75% of people see poverty displayed in the media all the time and 25% see it displayed sometimes, however when asked “How often do you contribute to making a difference after seeing images/videos of poverty in the media? e.g. sign petitions and donate.” The responses show that only 56.3% contribute to making a difference sometimes, 37.5% don’t contribute that often and a very small percentage contribute all the time. This suggests that even though people are constantly seeing images of poverty in the media, the step to take real action is not as high as it can be, highlighting that once people sympathize with the image, not a lot is done afterward.

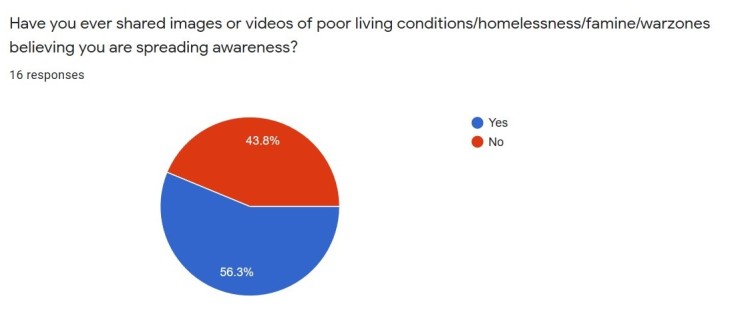

When asked “Have you ever shared images or videos of poor living conditions/homelessness/famine/warzones believing you are spreading awareness?” 43.8% said they have not while 56.3% said they have. I expected the number to be higher, but almost half the respondents had not shared any images or videos believing to spread awareness. This highlights that perhaps an image is not enough to create real change, perhaps images of poverty need to be connected to a specific cause or a campaign to ignite a greater response.

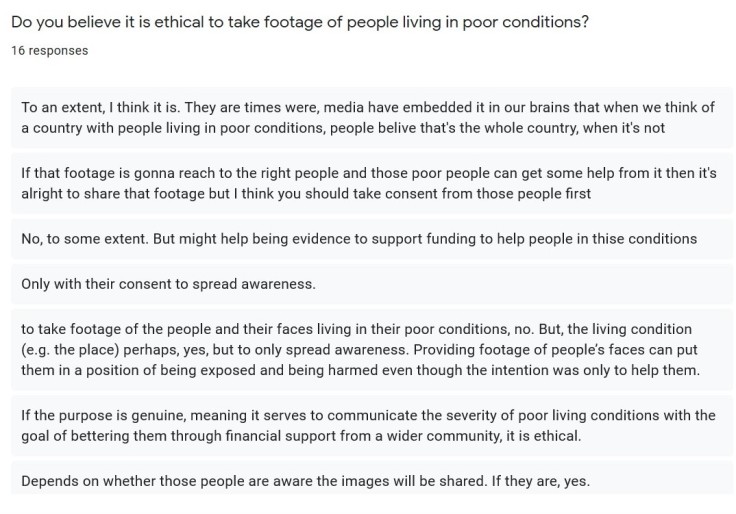

When asked “Do you believe it is ethical to take footage of people living in poor conditions?” most of the respondents agreed it was ethical, however to an extent or depending on the situation. Most of the respondents agreed that if consent was given, taking pictures or videos would not be as harmful. In my secondary research, I found that giving an opportunity to people living in poverty to have a say in what type images are taken creates a better environment for them where they don’t feel as dehumanized and embarrassed.

When asked “Do you believe it is ethical to take footage of people living in poor conditions?” most of the respondents agreed it was ethical, however to an extent or depending on the situation. Most of the respondents agreed that if consent was given, taking pictures or videos would not be as harmful. In my secondary research, I found that giving an opportunity to people living in poverty to have a say in what type images are taken creates a better environment for them where they don’t feel as dehumanized and embarrassed.

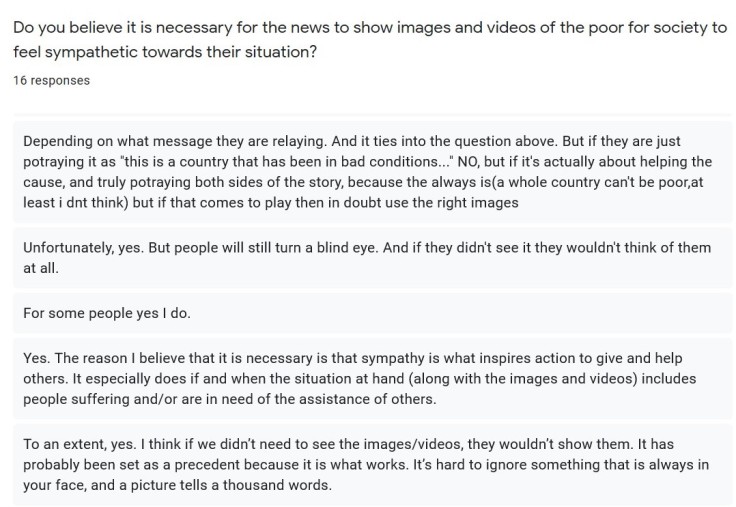

When asked “Do you believe it is necessary for the news to show images and videos of the poor for society to feel sympathetic towards their situation?” the majority of the respondents believed that it is easier to raise awareness about a situation if there is visual evidence. One of the respondents said:

“Yes. The reason I believe that it is necessary is that sympathy is what inspires action to give and help others. It especially does if and when the situation at hand (along with the images and videos) includes people suffering and/or are in need of the assistance of others.”

Another respondent said only if the image is helping a cause.

“Depending on what message they are relaying. And it ties into the question above. But if they are just portraying it as “this is a country that has been in bad conditions…” NO, but if it’s actually about helping the cause, and truly portraying both sides of the story, because the always is(a whole country can’t be poor, at least I don’t think) but if that comes to play then in doubt use the right images.”

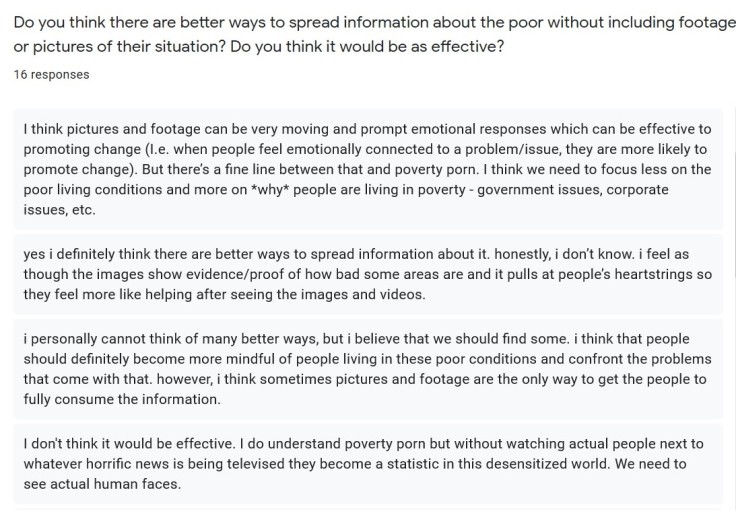

The last question I asked was “Do you think there are better ways to spread information about the poor without including footage or pictures of their situation? Do you think it would be as effective?” Most of the respondents believed images and videos are more effective in spreading information, however, one of the respondents made a point that blurring faces could be an effective way to get the visual while also giving people their privacy.

“I think seeing something visually is probably the strongest cue for an empathetic response, but maybe there can be more privacy for the people (blurring their faces, not including them but just their surroundings, etc.).”

Through this research I have found that media coverage of poverty can be extremely problematic if images are manipulated and consent is not given, however from what I have gathered, it would be hard to create an emotional response to events happening around the world if there was no visual evidence to ignite a sympathetic response. Images need to be taken tastefully and, in a way, where people are not exploited or manipulated. It can become problematic when those images create a different narrative to what is actually occurring, thus real change cannot occur.

References:

Bersak, 2006, Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future, Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003, Journal.

Estrin, 2015, An Embedded Photographer Empowers the Poor, The New York Times, Article.

M, Dolinar, P Sita, 2013, THE USE OF STEREOTYPICAL IMAGES OF AFRICA IN FUNDRAISING CAMPAIGNS, University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts, Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Slovenia, April 2013 edition vol.9, No.11.

N, Dortonne, 2016, The dangers of poverty porn, CNN, Updated 1526 GMT (2326 HKT) December 8, 2016.

Rare Historical Photos, N.P, The vulture and the little girl, Article.

R, Zguri, 2014, Ethical issues in photojournalism, Kolegji AAB Repoitory, Journal.

The Conversation, 2018, Images of suffering can bring about change – but are they ethical, Article.

The Guardian, N.P, Woman who was face of Live Aid laments price of fame 30 years on, Article.

UniteForSite, N.P, Ethics, and Photography in Developing Countries, Article.

Leave a comment